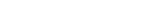

An international research consortium, affiliated with UNIST has succeeded for the first time in sequencing the reference genome of the Korean leopard, better known as the Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis). Scientists hope that their findings, described in the open access journal Genome Biology this week, will provide new insight into carnivory and how it impacts on genetic diversity and population size.

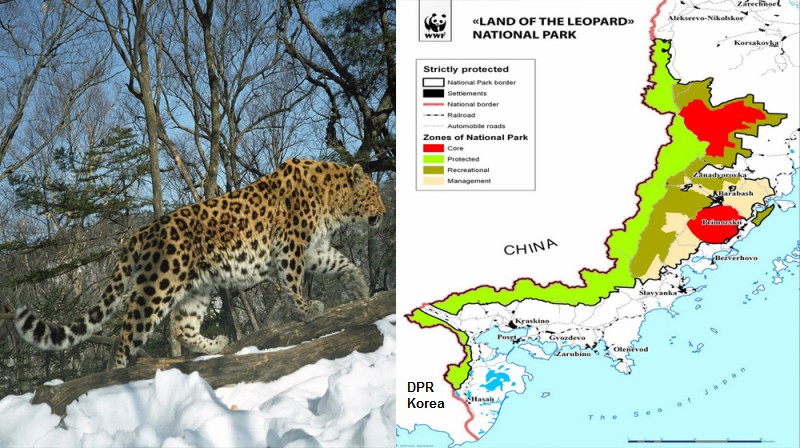

The Amur leopard is one of the ten living subspecies of leopard, native to the Primorye region of southeastern Russia and the Jilin Province of China, near the North Korea-China border. This solitary, nocturnal hunter was once widely distributed in South Korea until its population was nearly driven to critical extinction through decades of war and mass poaching. With fewer than 70 surviving in the wild today, they are particularly vulnerable to extinction because they have the lowest levels of genetic variation of any leopard subspecies, the researchers say.

Photo by the “Land of the leopard” National park in Russia.

This study has been jointly conducted by Prof. Jong Bhak from the School of Life Sciences of UNIST in collaboration with the National Institute of Biological Resources of South Korea. In the study, the research team developed a de novo genome assembly for a captive female Amur leopard before re-sequencing wild Amur leopards remain in the wild. Their study also used comparative genomics to search for signs of selection related to obligatory carnivory in the Amur leopard and other animals such as the domestic cat, lion, and cheetah — a feature found in a subset of mammalian species.

The research team began their investigations by mapping a reference genome of a leopard that died in the Daejeon Zoo of South Korea in 2012. They then decoded the genome sequence of a wild Amur leopard, for a comparison analysis of the two. In their study, the researchers used Illumina HiSeq instruments to sequence genomic DNA isolated from a captive female Amur leopard’s muscle. They then put the resulting sequence, along with synthetic long reads for two wild Amur leopards, together into a de novo assembly that spanned almost 2.57 billion base pairs and contained 19,043 predicted protein-coding genes.

After re-sequencing two more wild Amur leopards, the team analyzed the Amur leopard genomes alongside sequences from 18 other mammalian genomes. This includes eight carnivores (domestic cat, tiger, cheetah, lion, leopard, polar bear, killer whale and Tasmanian devil), five omnivores (human, mouse, dog, pig, and opossum) and five herbivores (giant panda, cow, horse, rabbit, and elephant).

Using the Amur leopard genome and comparing it to that of other mammalian genomes, the research team found that carnivorous species share two genes that play an important role in bone development and repair, which could drive selection for a diet specialized towards meat. For instance, cows could eat meat without it having a major impact on their health, but leopards eating grass would quickly die as they have evolved to survive on meat. This is something that are not apparent in omnivorous or herbivorous mammals.

“Carnivory related genetic adaptations such as extreme agility, muscle power and specialized diet make leopards such successful predators, but these lifestyle traits also make them genetically vulnerable,” Prof. Bahk said. “Our findings are expected to provide an important foundation for future preservation and restoration efforts of the Amur leopard.”

Relationship of Felidae to other mammalian species.

In the study, the researchers have identified 52 gene family expansions and 567 gene family contractions in the cat family compared with other carnivores, including expansions to gene families involved in muscle functions and movement. On the other hand, gene families involved in metabolizing starches and sugars were among those condensed in cats and other carnivores.

Meanwhile, the team saw an over-representation of motor axon and bone development genes across the 184 genes that appeared to be under positive selection in three or more carnivore genomes. Genes related to immune function appeared more likely to be under positive selection in the omnivorous or herbivorous animals.

The analyses also uncovered apparent adaptations to a meat-heavy diet in cat species, along with cat-specific conservation involving genes involved in light response, nerve impulse transmission, and other features. The study’s authors suggested that such findings may offer a refined look at dietary adaptations in cats and other animals, providing a framework for untangling animals’ broader biological responses to different food types and diet-related diseases.

“Cats are also a good model for studying health issues, such as human diabetes,” senior author Soonok Kim, a researcher at Korea’s National Institute of Biological Resources, said in a statement. “This new leopard genome reference is an environmental treasure that could help us understand these conditions further.”

The researchers hope that this Amur leopard reference genome will serve as a useful tool for understanding mankind’s physical capabilities at a genetic level, such as muscular strength and vision, as well as diseases that are thought to be affected by a prolonged mean-eating diet.

Journal Reference

Soonok Kim, Yun Sung Cho, Hak-Min Kim, et al., “Comparison of Carnivore, Omnivore, and Herbivore Mammalian Genomes with a New Leopard Assembly”, Genome Biology, (2016).