With increased study of bio-adhesives, a significant effort has been made in search for novel adhesives that will combine reversibility, repeated usage, stronger bonds and faster bonding time, non-toxic, and more importantly be effective in wet and other extreme conditions.

A team of Korean scientists−made up of scientists from Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) and UNIST−has recently found a way to make building flexible pressure sensors easier—by mimicking the suction cups on octopus’s tentacles.

In their paper published in the current edition of Advanced Materials, the research team describes how they studied the structure and adhesive mechanism of octopus suckers and then used what they learned to develop a new type of suction based adhesive material.

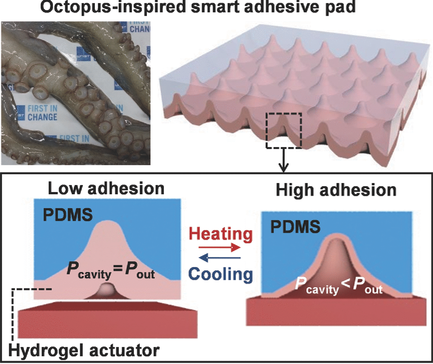

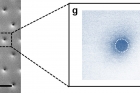

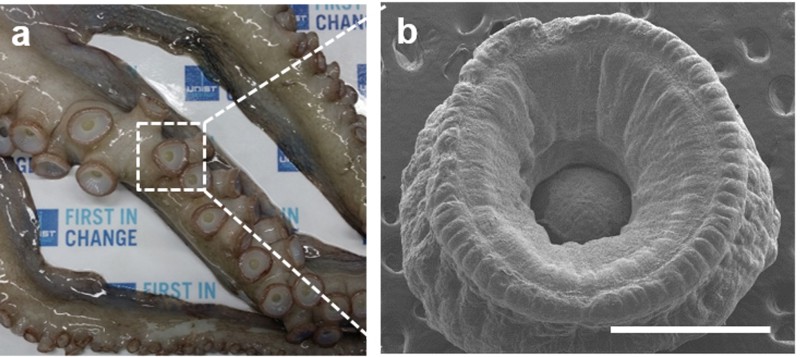

A photograph of octopus tentacle with suckers and a magnified SEM image of an octopus sucker (scale bar: 1 mm).

According to the research team, “Although flexible pressure sensors might give future prosthetics and robots a better sense of touch, building them requires a lot of laborious transferring of nano- and microribbons of inorganic semiconductor materials onto polymer sheets.”

In search of an easier way to process this transfer printing, Prof. Hyunhyub Ko (School of Energy and Chemical Engineering, UNIST) and his colleagues turned to the octopus suction cups for inspiration.

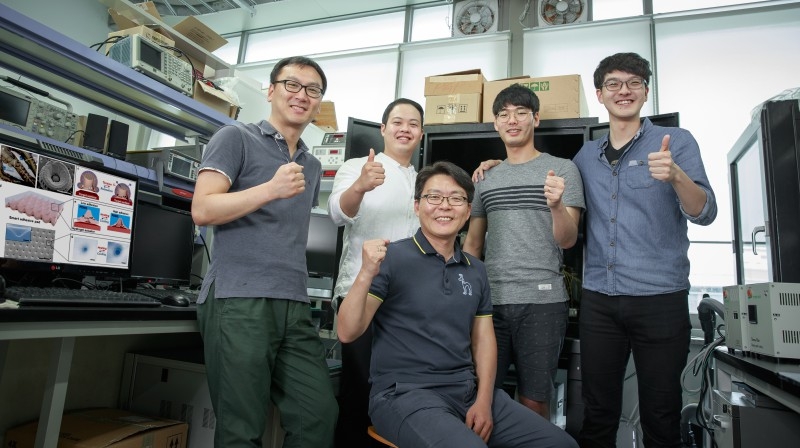

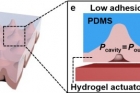

An octopus uses its tentacles to move to a new location and uses suction cups underneath each tentacle to grab onto something. Each suction cup contains a cavity whose pressure is controlled by surrounding muscles. These can be made thinner or thicker on demand, increasing or decreasing air pressure inside the cup, allowing for sucking and releasing as desired.

By mimicking muscle actuation to control cavity-pressure-induced adhesion of octopus suckers, Prof. Ko and his team engineered octopus-inspired smart adhesive pads. They used the rubbery material polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) to create an array of microscale suckers, which included pores that are coated with a thermally responsive polymer to create sucker-like walls.

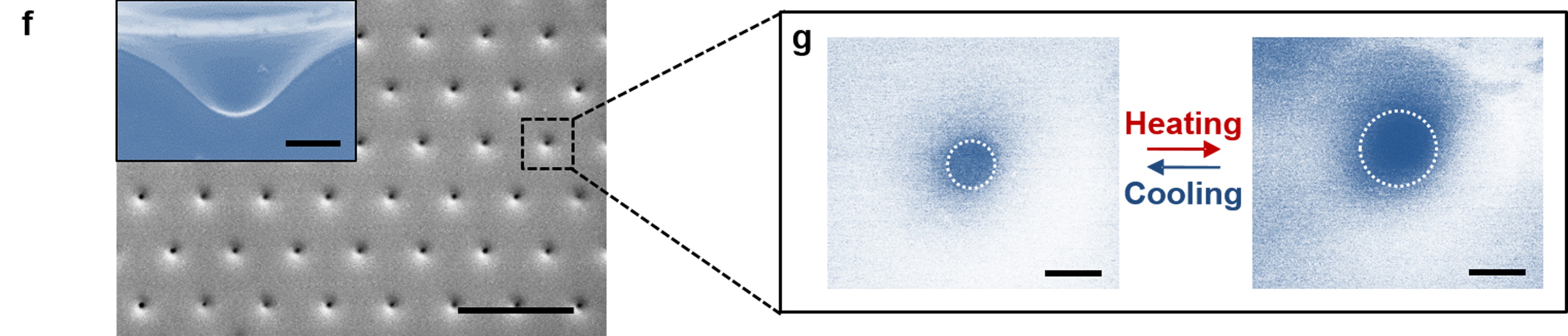

The team discovered that the best way to replicate organic nature of muscle contractions would be through applied heat. Indeed, at room temperature, the walls of each pit sit in an ‘open’ state, but when the mat is heated to 32°C, the walls contract, creating suction, therby allowing the entire mate to adhere to a material (mimicking the suction function of an octopus). The adhesive strength also spiked from .32 kilopascals to 94 kilopascals at high temperature.

The team reports that the mat worked as envisioned—they made some indium gallium arsenide transistors that sat on a flexible substrate and also used it to move some nanomaterials to a different type of flexible material.

Prof. Ko and his team expect that their smart adhesive pads can be used as the substrate for wearable health sensors, such as Band-Aids or sensors that stick to the skin at normal body temperatures but fall off when rinsed under cold water.

Journal Reference

Hochan Lee, Doo-Seung Um, Youngsu Lee, Seongdong Lim, Hyung-jun Kim, and Hyunhyub Ko, “Octopus-Inspired Smart Adhesive Pads for Transfer Printing of Semiconducting Nanomembranes”, Advanced Materials, (2016).